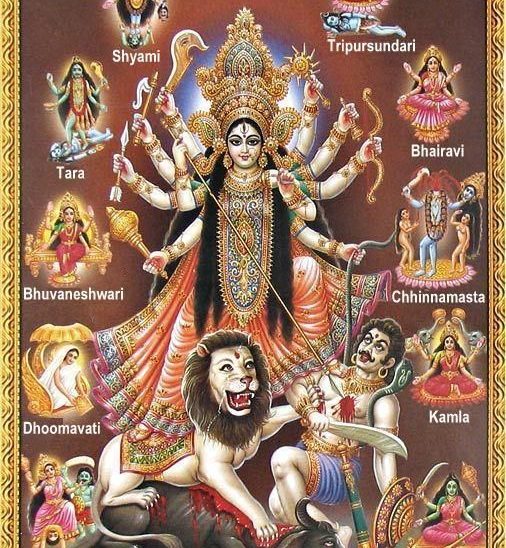

Shaktas believe, “the one Truth is sensed in ten different facets; the Divine Mother is adored and approached as ten cosmic personalities,” the Dasa-Mahavidya.

The ten Mahavidyas symbolize distinct aspects of divinity committed on directing the spiritual seeker toward liberation. For the devotionally minded seeker, these forms can be approached in a spirit of reverence, love, and increasing intimacy. For a knowledge-oriented seeker, these same forms can characterize numerous states of inner awakening along the path to enlightenment.

The Das Mahavidyas are Wisdom Goddesses: ‘Das,’ means ten, ‘maha,’ means great, and ‘vidya,’ means wisdom. The Das Mahavidyas are believed to be forms of Divine Mother Kali, who is the first of the Mahavidyas. Each Wisdom Goddess has Her own name, story, quality, and mantras. They are all AVATARS of Goddess Parvati and They are: KALI, TARA, TRIPURA SUNDARI (or Shodashi), BHUVANESWARI, CHINNAMASTA, DHUMAVATI, BAGALAMUKHI, MATANGI and KAMALA.

KALI

Kali, the first of the Das Mahavidyas represents the power of consciousness in its highest form. She is at once supreme power and ultimate reality, emphasizing the essential Tantric teaching that the power of consciousness and consciousness itself are one and the same.

From the Absolute to the relative and from the relative to the Absolute, Kali represents the power of transformation. For us, who erroneously think ourselves to be mere mortals, She holds out the assurance of transformation from the human to the Divine.

TARA

Second after Kali, Tara closely resembles Kali. Just as Kali Herself has many unique characteristics, so does Tara. Tara is renowned both in Tibetan Buddhism and in Tantric Hinduism, and Her many aspects include forms that are either peaceful (saumya) or ferocious (ugra). The Hindu Sakta Tantra seems to prefer the fierce forms. Tara’s name is derived from ‘tri,’ which means “to cross.” One of Her appellations is ‘Samsaratarini,’ “She who takes across the ocean of worldly existence.” Tara is thus the all-gracious saviour.

So close are the representations of Tara and Kali that often their identities blur. Of course, divinity is a single reality, and that has been proclaimed from the time of the Rigveda onward: “Truth is one; the wise call it by various names.” Both Kali and Tara are deeply associated with death and dissolution. While Kali is often said to be the power of time (kala), that inevitably causes all created things to perish, Tara is more often associated with fire, and particularly the fires of the cremation ground. One of Her names is Smasanabhairavi, “the terrible one of the cremation grounds.” It is vital to keep in mind that fire symbolizes not only destruction but also purification and transformation.

TRIPURASUNDARI

Tripurasundari is sometimes spoken of as an adimahavidya, or primordial wisdom goddess, which puts Her in the company of Kali and Tara as representing one of the ultimate encounters of reality. She is not the ultimate, absolute, or ‘nirguna,’ state bereft of all qualities; still, She represents the experience of consciousness in a high state of divine universality. Her other names include Sodasi, Lalita, Kamesvari, Srividya, and Rajarajesvari. Each of these emphasizes a particular quality or function.

Tripurasundari represents the state of awareness that is also called the sadasivatattva. It is described as “I am this,” (aham idam).

Tripura Sundar’s sadhana is therefore the purification of our awareness—purging the mind of unworthy thoughts and the patterns of thinking that motivate them, acknowledging beauty everywhere, seeing the extraordinary in the routine, and escalating to the belief that nothing is alien to ourselves. As the Upanishads teach, “All this universe is truly Brahman” (sarvam khalv idam brahma); so too is this Self (ayam atma brahma).

BHUVANESWARI

The fourth Mahavidya is Bhuvanesvari, whose form closely bear a resemblance to that of Tripurasundari. Even more than the goddess who is beautiful in the three worlds or surpasses them, Bhuvanesvari is categorized with the manifest world and our experience of it.

Her name consists of two elements: ‘bhuvana,’ which means this living world—a place of energetic activity—and ‘isvari,’ which means the female ruler or sovereign. The name Bhuvanesvari is most often interpreted as “Mistress of the World,” but ‘bhuvana,’ is more than the earth we stand upon. It is the entire cosmos, the ‘bhuvanatraya,’ comprising the heavens, the atmosphere, and the earth.

Practically speaking, Bhuvanesvari, by Her ubiquity and identification with the universe, encourages us to nurture an mindset of universality. Any religion that lays claim to acquiring the absolute truth is indulging in a hazardous illusion. All religions link humankind to a single reality that lies beyond this world of our petty differences yet abides in every heart and mind. Some choose to call this reality God or Heavenly Father or Divine Mother, but in truth He, She, or It is that which cannot be named, for to name is to limit, and who are we to limit the Illimitable? And why? For our own personal comfort or satisfaction, either individually or collectively? Does it serve us better to cling to our own parochial ideas of the Divine and ever to squabble among ourselves? Or to open ourselves to the Infinite, which we can never describe, but which in truth we are.

CHINNAMASTA

Chinnamasta (“She who is decapitated,”), is a form of the Divine Mother shown as having cut off Her own head. The blood that spurts from Her neck flows in three streams—one into Her own mouth and the others into the mouths of Her two female attendants, Dakini and Varnini. At the same time, Chinnamasta stands on the body of another female figure who is copulating with a male who lies beneath Her.

Chinnamasta’s symbolism relates overwhelmingly to ridding ourselves of wrong ideas and the limitations imposed on us by ignorance of our true nature. Despite the violence of the imagery, it is important to note that Chinnamasta does not die; She is very much alive. The message here is that the Self is indestructible (akshara) and eternal (nitya) by its very nature (svabhav).

In practical terms, if the act of decapitation is viewed as an act of self-sacrifice, then the message for us is that selfless acts will not hurt us. To the contrary, any selfless act will indeed diminish the ego, but what is the ego? Only the wall of separation, limitation, and ignorance that keeps us imprisoned by our own false sense of who we are. Chinnamasta, then, in the act of self-decapitation by the sacrificial knife urges us to relinquish a smaller, powerless identity for one that is infinitely greater and all-powerful.

BHAIRAVI

The name Bhairavi means “frightful,” “terrible,” “horrible,” or “formidable.” The basic idea here is fear. Ordinarily we associate fear with darkness. It is not uncommon to be afraid of the dark, or rather of the dangers that lurk there unseen, but that is not the sort of fear that Bhairavi provokes, for She is said to shine with the effulgence of ten thousand rising suns.

Though Bhairavi can be disconcerting or even downright frightening, She is in the end beneficent. Again, we are reminded that She is the colour of fire, and what does fire do? At the physical level it burns. Its blaze of heat and light consumes whatever has form, and in this awesome manifestation of destructive power it is both magnificent and terrifying. Yet when controlled, fire can be beneficial, warming us when we are cold, cooking our food, and so on.

It is often said that Bhairavi represents divine wrath, but it is only an impulse of Her fierce, maternal protectiveness, aimed at the destruction of ignorance and everything negative that keeps us in bondage. In that aspect She is called Sakalasiddhibhairavi, the granter of every perfection.

DHUMAVATI

If Bhairavi represents overwhelming brilliance, Dhumavati personifies the dark side of life. We know from our own experience that life can be exhilarating, joyful, and pleasant—something we want to embrace and live to the fullest. But at other times we find that this same life can be depressing, sorrowful, painful, and frustrating. At such moments we respond with pessimism, sadness, anxiety, or anger. It is then that we no longer want to embrace life but rather to avoid its misery.

This is where Dhumavati comes in. Her name means “She who is made of smoke.” Smoke is one of the effects of fire. It is dark and polluting and concealing; it is emblematic of the worst facets of human existence. The concepts embodied in Dhumavati are very ancient, and they have to do with keeping life’s inevitable suffering at bay.

The image of Dhumavati, old and ugly and alone and miserable in Her cart of disempowerment, tells us to cultivate a sense of detachment. Note that Dhumavati holds a bowl of fire in one hand and a winnowing basket in the other. The fire symbolizes inevitable cosmic destruction: all things shall pass away. The winnowing basket, used to separate grain from chaff, represents ‘viveka,’ mental discrimination between the permanent and the fleeting. Even though Her stalled cart represents an external life going nowhere, Dhumavati empowers us inwardly to reach for the highest, and there is nothing to stop us once we are resolved. In the end, She points the way to liberation.

BAGALAMUKHI

Of all the Mahavidyas, Bagalamukhi is the one whose meaning is the most elusive. Her symbology varies widely, and its interpretation shows little consistency. One of Her common epithets is Pitambaradevi, “the goddess dressed in yellow.” Her ‘dhyanamantras,’ also emphasize the yellow colour of Her complexion, clothing, ornaments, and garland. Her devotees are instructed to wear yellow while worshiping Her and to employ a mala made of turmeric beads. Even Her few temples are painted yellow. There is no consensus on what the colour yellow is supposed to mean either. The most plausible explanation out of several is that yellow, being the colour of the sun, representing the light of consciousness.

Bagalamukhi is consistently associated with siddhis, which are yogic powers with magical properties. For a genuine spiritual aspirant such powers are obstacles to be avoided. That said, one such power is ‘stambhana,’ the power to immobilize, to paralyze, to restrain an enemy.

Stambhana in the highest sense is yoga. After duly observing the ethical practices of yama and the ennobling disciples of niyama, we are ready for asana. Sitting quietly stops the motion of the body, which in turn calms the metabolic functions and prepares us to quiet the mind. The remaining states of pratyahara, dharana, dhyana, and samadhi are a continuum of ever decreasing activity, culminating in the experience of the Self as pure, unconditioned consciousness. Pulling us by the tongue, Bagalamukhi draws us there.

MATANGI

At first glance Matangi looks very much like Sarasvati. The main point of similarity is the vina that She plays. Like Sarasvati, She may be shown holding a book and a japamala as well. Together these symbolize the interrelated aspects of sound, knowledge, and power. The sound of the vina represents creativity, which is the power of consciousness to express itself. The mala also represents the power of sound, but in the form of the mantra. The book stands for the wisdom and knowledge transmitted through the word. The parrot that accompanies Matangi also has associations with speech.

Like Bagalamukhi, Matangi is often associated with yogic or magical powers that can be invoked to exert influence over our environment or over other people. Rather than to seek mastery over others, it is higher and nobler by far to seek control over the impulses of one’s own lower Self.

In Tantric teaching the word for impurity is ‘mala.’ Mala arises through the atman’s association with maya, the Divine’s own power of limitation. The imperfect finite soul is only a contracted form of the perfect, infinite Self. Mala is the impurity of our finitude, and it takes three forms. Our actions are never free and spontaneous; they always bow to the conditioning that binds us, and their effects in turn prolong the bondage.

As long as the malas colour our awareness, they hold us captive. As long as we chase the conventional notions of purity and piety and shun their opposites, we are caught up in a reactive chain. Matangi’s example teaches us to face our false notions head on and to be free.

KAMALA

The ten Mahavidyas begins with Kali and ends with Kamala, portrayed as making the gestures of boon-giving and fearlessness. She sits on a lotus and holds lotus blossoms in Her two upper hands. Even Her name means “lotus.” She is flanked by two elephants. Obviously, Kamala is Lakshmi, who is portrayed in the identical manner, but in the context of the Mahavidyas, there are also significant differences.

Kamala is not a divine consort but the independent and all-supreme Divine Mother. She is not the spouse of any male deity. Interestingly, She is rarely identified with the other female forms found in orthodox Vaisnavism, such as Sita, Radha, or Rukmini. If any consort names are ever applied to Her as epithets, they are Saiva names such as Siva (“the auspicious one,”), and Gauri (“She who is gently radiant,”). However, Kamala is not completely auspicious or one-sided. Sometimes She is called Rudra (“the howling one,”), Ghora or Bhima (“the terrifying one,”), or Tamasi (“the dark one,”). Like Kali, the Tantric Kamala embraces the light and the darkness, for She is the totality.

These tantric Avatars of the sacred feminine are states of spiritual awakening that we experience within our own minds and hearts along the course of our journey back to the Divine. How often we’ve heard it said that God is love. Lakshmi or Kamala represents that love. To be saturated with the presence of Kamala is to become an embodiment of divine love. Then we come to understand Her great secret: love is unique and unlike anything else, for the more of it you give, the more of it you have. And with this great secret Kamala offers us a direct path to the Divine.

SUJATA NANDY WORLD GURUKUL

www.sujatanandy.com